|

November 10, 2005

T.O. History Revisited: The Gooderham and

Worts Factory Complex

By Bruce Bell

Bruce Bell is the history columnist for the Bulletin, Canada’s

largest community newspaper. He sits on the board of the Town of

York Historical Society and is the author of two books ‘Amazing

Tales of St. Lawrence Neighbourhood’ and ‘TORONTO: A

Pictorial Celebration’. He is also the Official Tour Guide

of St Lawrence Market. For more info visit brucebelltours.com

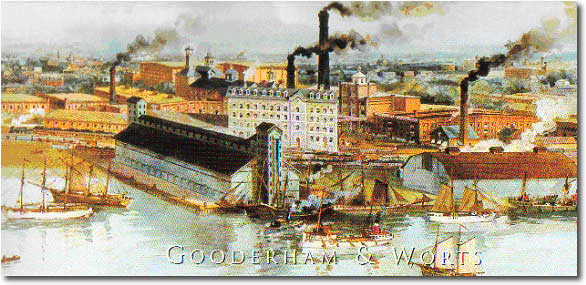

The Gooderham and Worts Distillery (Trinity and Mill St. in the

Parliament and Front St. vicinity) is without a doubt the best preserved

19th century factory complex in the country. What rescued its unparalleled

Victorian Industrial grandeur from being demolished, during the

riotous heyday of urban renewal in the 1960's, was the fact that

it kept functioning as a distillery up until the 1990's. Its walls

and cobblestone paths do not only encapsulate the surrounding neighborhood’s

lustrous history, but that too of Toronto, Canada and the British

Empire.

The first mill to be erected on that site was back in 1831, when

James Worts, a Yorkshireman, built a windmill with a millstone to

grind wheat into flour on the shores of what was then our waterfront.

That first mill-stone is today displayed prominently on a pedestal

on the grounds of the complex with a bronze plaque detailing its

history. In 1832 William Gooderham, also arriving from Yorkshire,

brought with him money and 54 family members to help his brother-in-law

expand the business, to be known then as Worts and Gooderham. One

of the first things they did was to replace the wind-powered sails

on the windmill with a steam engine after realizing the breeze off

the lake wasn't powerful enough.

In 1834 James Worts, despondent over the death of his wife in childbirth,

committed suicide. William Gooderham, together with his 7 sons (his

6 daughters, like other well-bred women of the 19th century, were

not encouraged to work) and the nephews left orphaned after the

death of his sister and James, took control of the factory and re-named

it Gooderham and Worts. The 'Worts' in the name of the factory is

not named for James Sr. but for his eldest son, James Gooderham

Worts, who took over his fathers' side of the business. Very few

of the 19th century books I use for part of my research ever mention

that James Worts committed suicide, it's only in the late 20th century

that this knowledge comes into print. What I can conclude however,

is that the people of early York looked upon James Worts as being

peculiar, a quixotic character, especially after he announced to

them he was going to build a windmill. Some 40 years after Worts'

death, James Beaty, an early pioneer, told friends that he came

upon Mr. Worts standing in the middle of the bush, on the site that

was to become the distillery, and was 'rambling on, apparently without

purpose'.

Mr. Beaty goes on to say 'Brooding inside Mr. Worts' brain seemed

to be a vision for what York was capable of becoming and a windmill,

though viewed as eccentric by the early upright citizens of York,

was to be just the beginning'. It would seem that James Worts was

a tortured man ahead of his time. Mr. Worts' Windmill, with its

non-functioning sails, was to become a cherished folly until it

was ultimately demolished in 1856 after being severely damaged in

a storm a few years before.

In 1837 the company began distilling the wheat by-products into

booze for a thirsty city. Toronto for all it's soon to be Victorian

idealism and demeanor was a saloon-laden town with a tavern for

every 100 people. Beer was drunk then, like water is today. Mothers

fed their babies beer, kids drank beer openly in the streets, magistrates

and clergy drank on the job and no wonder, water then was filthy

and tasted horrible. Dead horses, cats, dogs, manure and daily garbage

were thrown onto the ice of Lake Ontario and when the ice melted,

the sewage would sink into the lake where upon people would drink

the stuff untreated. That in turn led to cholera outbreaks, killing

thousands. Beer seemed a nice alternative to death.

The 45 structures that today make up the factory site were begun

in 1859; the oldest being the gray limestone gristmill and distillery

that can be seen from the Gardiner Expressway. It, like the windmill

had been, became a landmark at the eastern end of the harbour.

Modern view of the Distillery District

The building was state-of-the-art when built. It housed an elevator

on the south side that raised grain from rail-cars to the upper

floors. At its eastern end was a 100-horsepower steam engine that

ran eight sets of grindstones and the western end held the distillery

apparatus. The noise inside must have been deafening. Under the

supervision of architect David Roberts Sr., five hundred men worked

on the construction, with four massive lake schooners being used

to move the stone from Kingston quarries. The building was finished

in 1860, at a cost of a then staggering sum of 25,000 dollars, making

it the most expensive building project in Toronto at the time. In

1863 the malting and storage buildings, the ones with the cupolas

rising from their roofs, and the massive square shaped warehouse

(now used as storage for The City of Toronto) at the corner of Trinity

and Mill Streets, were built.

In 1869 a keg of benzine broke open that caused a huge explosion

and fire to spread up the elevator shaft of the main building destroying

the wooden interior (later re-built) but left the gray limestone

exterior standing.

In 1870, the Pure Spirits Building, one of the most charming buildings

Toronto has left from this period, was built. Made of red brick,

it has French doors leading out onto a wrought iron balcony on its

second floor.

Solid brick piers or buttresses, used to support tall panels of

plate glass, rise above the roof, the building was used for processing

extremely flammable pure alcohol and the west-facing glass wall

admitted as much natural light as possible thus eliminating the

need for open gas jet lamps.

Three events of the mid 19th century inspired the tremendous growth

of Toronto and the financial boom of the Gooderham and Worts family

fortunes. The first was the Great Fire of 1849 that destroyed much

of then downtown Toronto and resulting in the rebuilding of the

city, as we know it today. The second was the coming of the railroad,

which made for easier access of products streaming in and out of

the city.

The third was a fungus which ruined the crop of potatoes that sustained,

however meager, the people of Ireland. Toronto's population swelled

with starving Irish refugees escaping the horrors of the Great Potato

Famine back home. Toronto had, before these events, a small population

of about 10,000, mostly of British Protestant descent. By 1851 the

population grew to 30,000, with 37% being Irish. They worked mostly

as servants and as labourers in the many mills, including Gooderham

and Worts that sprang up along the Don River.

Distillery District at night

The newly arrived Irish, both Catholic and Protestant, settled

into the area surrounding King and Parliament Streets just up the

road from the Distillery. This area was to expand northwards and

because of the cabbages that were grown in abundance it came to

be known as Cabbagetown. In 1985 JMS Careless wrote in- Gathering

Place, People and Neighbourhoods of Toronto- of Cabbagetowns’

beginnings....'Blight stemmed from the dirt, debris and fumes of

factories close at hand; their industrial dumps and coal-heaps not

to mention stockyards, livery stables, cow-barns and all their refuse.

Other major offenses were the reeking hog pens of the big William

Davies meat packing plant and the cattle herded at Gooderham and

Worts to feed on used brewing mash. All this and the dangers of

choked privies, overflowing cesspools and contaminated wells in

a district thinly served by the civic water system.' Yuck!

In 1843 William Gooderham, built the Little Trinity Church on King

E because at the time St. James Cathedral at King and Church used

to charge a pews fee and many working class Anglicans couldn't afford

to pay it. The Catholics too had their own Church, St. Paul's, on

Power and Queen E, built in 1826 and re-built in 1887 as the magnificent

St. Paul's Roman Catholic Church that stands there now. As their

fortunes grew the Gooderhams, beginning in 1885, started to build

worker-cottages on Trinity and Sackville Streets (still standing)

but they weren't the only benevolent distilling family in the district.

In 1848 the Protestant Irish of this neighbourhood were too poor

to send their children to the up-scale school at St. James and free

education was years off, so brewer Enoch Turner built what is today

the oldest standing school building in the city, The Enoch Turner

School House on Trinity Street.

There it was, a perfect English-style factory town, stench and

all, on the edge of a great city. What more could a working man

want? Home, factory, school, church and tavern all within walking

distance. The Gooderhams, with all their wealth and power continued

to live amongst their workers in a house, now demolished, on the

NW corner of Trinity and Mill Streets.

In the late 1800's as Toronto was becoming more class conscience

and the dividing lines between commercial and residential areas

became more defined,

George Gooderham, son of William, who had now taken over the family

business, built for himself an impressive mansion (still standing)

in the fashionable Annex area on the NE corner of Bloor and St.

George in 1889.

George, now in full control of the family business, developed it

into a financial and commercial empire becoming not only the richest

man in Toronto but in all of Ontario. As the distillery flourished

he enlarged its facilities and began to expand his own interests

that included the Toronto and Nipissing Railroad, Manufactures’

Life Insurance, The King Edward Hotel and philanthropic enterprises

like U of T and The Toronto General Hospital. In 1882 he became

the president of The Bank of Toronto (forerunner to The TD). What

he needed now was an impressive office building. In 1891 he commissioned

David Roberts Jr., the son of the architect who had built the distillery,

to erect what is today the crown jewel and the most photographed

structure in our neighbourhood, the Gooderham Building, also known

as the Flatiron at the junction of Church, Front and Wellington

Streets (today owned and lovingly restored by Anne and Michael Tippin).

There, on the fifth floor, underneath the green cone-shaped cupola,

he set himself up in an office that overlooked not only the busy

intersection below but also everything and everyone he held command

of, the original Big Brother. From the ships in the Harbour and

the trains on the Esplanade, to the Distillery in the distance,

all were within his sight. Then he had commissioned, what was to

become one of the great legends of our neighbourhood, a tunnel to

pass underneath Wellington Street to connect with the Bank of Toronto

(where Pizza-Pizza now stands). Even though it's been bricked up

at both ends and cable, phone and sewer lines criss-cross it, Mr.

Gooderham's tunnel still exists.

When he died in 1905 his funeral at St. James Cathedral, against

his last wishes for a small affair, was one of the largest the city

had seen. He was a great benefactor, builder and much loved man

to the people of Toronto who lined the streets to show their respect

as his cortege made its way to St. James Cemetery.

In 1920, the distillery, founded by 'the famous Mr. Gooderham as

he was commonly known, and by the tragic Mr. Worts, was bought by

the Hiram Walker Company. Today its ultimate fate still hangs in

the air, with condos, apartments and lofts springing up around it,

the Gooderham and Worts complex is used mostly as a film set and

no wonder, it's Old World ambiance and Hollywood-back-lot atmosphere

is picture perfect. To walk around within its enclave, when no one

is around as I did recently, is to journey to another era. You can

just make out through the centuries old dust that is the mist of

time, the young 19th century immigrant, standing before its main

gates, lunch box in hand, about to enter his first day on the job,

not knowing what to expect from this new world that lay before him.

With that kind of history, could there be a more perfect place for

a much needed Toronto Museum?

[Editor's note: This article was originally written some time

ago. Since then the Historic Distillery District has recently become

one of the most vibrant entertainment areas in Toronto, with restaurants,

breweries, galleries, book stores and artisans' workshops. More

info is available at http://www.thedistillerydistrict.com/htmlsite/index.html]

Useful Books:

Here is Bruce's brand-new book about Toronto

Related Articles:

Here's my story about Bruce Bell's St.

Lawrence Market Tour

Bruce's history of Toronto Island

- Part I

Bruce's history of Toronto Island

- Part II

Bruce's history of Toronto's St.

James Cathedral

Bruce's history of The Royal

York Hotel

|